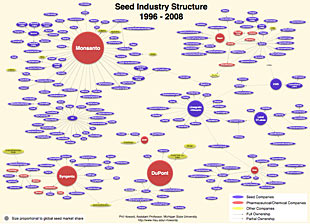

Over the past 100 years, the worldwide trend in seed production and distribution has been towards consolidation, as large seed companies purchase most of the smaller independent ones. By 1924, large companies had convinced Congress to cut the seed distribution programs of land grant universities (like WSU) and over the decades those universities came to see their primary role as training plant breeders to do research for private industry. Today, according to ETC Group, the top 10 multinational seed firms control half of the world's commercial seed sales (a total worldwide market of approximately US $21 billion per annum). Corporate control and ownership of seeds—the first link in the food chain—has far-reaching implications for global food security. Today most seed availability is controlled by companies that have no historical seed interests. They are chemical and pharmaceutical firms, and what used to be open sources of seed are intensely concentrated in the hands of a few very powerful multinational corporations with no regulatory oversight, including Monsanto, Syngenta, Dupont, Dow and Bayer.

Over the past 100 years, the worldwide trend in seed production and distribution has been towards consolidation, as large seed companies purchase most of the smaller independent ones. By 1924, large companies had convinced Congress to cut the seed distribution programs of land grant universities (like WSU) and over the decades those universities came to see their primary role as training plant breeders to do research for private industry. Today, according to ETC Group, the top 10 multinational seed firms control half of the world's commercial seed sales (a total worldwide market of approximately US $21 billion per annum). Corporate control and ownership of seeds—the first link in the food chain—has far-reaching implications for global food security. Today most seed availability is controlled by companies that have no historical seed interests. They are chemical and pharmaceutical firms, and what used to be open sources of seed are intensely concentrated in the hands of a few very powerful multinational corporations with no regulatory oversight, including Monsanto, Syngenta, Dupont, Dow and Bayer.

Organic farmers need to be able to select and breed their own seed to develop varieties that thrive in their particular climates. This is especially important in times of climate destabilization. The corporations want farmers all over the world to come to them for seed, but it doesn't take much imagination to understand that a corporation, whose motivation is profit, will not take the time or energy to develop or improve organic seed adapted to a particular climate. All the big seed companies are developing new varieties in the lab, through genetic modification, rather than in the field, as farmers have for centuries. (Image courtesy of Philip H. Howard, Associate Professor, MSU)

With consolidation, many seed varieties and heirloom seeds have been phased out. Heirloom seeds are those that have been passed down through generations for at least 50 years, and are now in some danger of extinction. They are all open-pollinated.

Many heirloom seeds come from immigrants that brought seed from “the old country” to add to the cultural, culinary and agricultural diversity of the new world. “Because of consolidation and concentration in the seed industry, there has been loss of variety and loss of heirloom varieties,” according to Matthew Dillon, a founder of the Organic Seed Alliance of Port Townsend. "But the real concern from our perspective was that the skills of working with seed are being lost even more than the seed themselves. The work of farmers and gardeners who created the diversity we have today is no longer being regenerated—selecting varieties, seeing anomalies you like and saving it." [Edible Seattle, March/April 2011, vol. 4/no.2, page 30]

Many heirloom seeds come from immigrants that brought seed from “the old country” to add to the cultural, culinary and agricultural diversity of the new world. “Because of consolidation and concentration in the seed industry, there has been loss of variety and loss of heirloom varieties,” according to Matthew Dillon, a founder of the Organic Seed Alliance of Port Townsend. "But the real concern from our perspective was that the skills of working with seed are being lost even more than the seed themselves. The work of farmers and gardeners who created the diversity we have today is no longer being regenerated—selecting varieties, seeing anomalies you like and saving it." [Edible Seattle, March/April 2011, vol. 4/no.2, page 30]

Gardeners, as well as farmers, may lose the ability to plant what they want because seed diversity is so diminished under the current system of consolidation. Interested individuals should contact Seed Savers Exchange in their area.

Today, more and more organic farmers realize they must take responsibility for their own seed production. They must cooperate to share seed, get training in seed selecting, work to restore seed varieties from the past, and keep current and future varieties vigorous. Organic Seed Alliance is a great resource for farmers for information about seed.

At Nash’s we grow several heirloom varieties of apples, kales, chards, garlic and beets.